Good morning 👋

And welcome back from Thanksgiving. It’s officially December, and that means we’re approaching recap season.

As of this morning, we’ve put out 174 newsletters this year along with hundreds of other takes through my personal Twitter (linked).

Here are 75 of the biggest ideas from 2025 that we think will matter the most in the years ahead.

Let us know which one (if any) you think is most important.

P.S. This is a long one and will get clipped by Gmail.

If you want to get all of our biggest ideas from the year, read online by following the button above.

Big breakdown

Big ideas

There’s a punchy take that the Musks of the world are created not by - as say, your run-of-the-mill Ivy League parents, are - a compounding of good decisions, but rather by a series of going all in on black, every time. More technically: “you get to the tail by increasing the variance (or the scale) rather than raising the expectation”.

Investing in alternatives is alpha; investing in publics is beta. Within alternatives, investing in consensus backers is beta; everything else is alpha. (LINK)

The increasing returns to scale of winner-take-all markets means the big get bigger.

The top 10 biggest companies globally already have gone from 31% of the total market (in 2015) to 47% today. I’m sure you’ve seen those graphs showing companies with increasing speed to 100m+ users or increasingly few employees to $100m+ ARR. The kurtosis for startup successes is obscene. The outliers have kept getting bigger, now they’re doing so faster and more efficiently. (LINK)

Venture is built to make money in disequilibrium.

Most companies, funds, and vintages are bust, some are milli-baggers. A high loss ratio is a feature. It’s the exact opposite of Buffet being perfectly willing to trade away a big payoff for a certain payoff. (LINK)

Media today = be everywhere.

GPs + other investors are expected to constantly be putting out quality content. Podcasts and newsletters are experimented with internally to see what works so they can pour more into those channels. (LINK)

The modern ecosystem funnel: Content —> subscriptions —> engagement —> invitations.

The bottom of the funnel for content is to meet with interesting people. You should be writing for a specific type of person that you want to meet with. Generic, mass appeal slop content gets ignored or attracts the wrong batch of people. (LINK)

Statistically speaking, 10xing a diversified fund is only 2x harder than a concentrated fund, but with a massively higher luck surface area.

Venture is a power law game, and we all know that only when you get the really big winner you do very well. If someone offered you 3.5 times more shots for each shot you take and you’d only have to find only a 2x bigger outcome, you’d take the deal every single time. (LINK)

Results from your first fund will largely be graded based on access.

Especially as a pre-seed / seed fund, you will not be expected to show distributed capital (yet). You will be expected to be able to craft a narrative around how the existing portfolio will shape into distributed capital in the future, and that story starts with proving your ability to win allocations to special companies, early. (LINK)

You will get no re-ups if you deviate from the story you told initial LPs.

If you raise on the idea of building a curated portfolio of pre-seed founders, and your average entry price is $25m+ post, you’ve violated your fiduciary duty to your LPs. (LINK)

Attention =/= trust.

In the same vein, not all audiences are created equal. Eyeballs are a proxy for distribution, but conversion rate is a proxy for trust. (LINK)

Every fund is now expected to produce content, create ecosystems, and be able to tangibly show your inbound funnel (thanks, a16z).

At the same time, I would argue that some of the best investors of all time have been the most secretive with their thinking. (LINK)

Raising capital and deploying capital are two completely different skill sets.

Fundraising is narrative-driven. Investing is pattern recognition and conviction. Almost nobody is elite at both. You’ll need to learn the one you’re weaker at fast, or hire for it. (LINK)

“If the founder doesn’t know who you are AND if you don’t know the company’s updates in the last two quarters, you don’t know the founder … You’re forgettable. And that’s a cardinal sin of firm-building.”

You can’t be everything to everybody. The earlier you commit to your wedge (saying “yes” before consensus, operating ability to help, customer intros “guy”, recruiting / talent “guy”, etc.), the better off you are. (LINK)

Firm-building means you plan to grow the firm. That where you are today is not where you want to stay forever as a GP.

Thrive started as a $5m fund. You need a plan to scale, but scale comes in two forms: 1) scaling coverage and running the same playbook, better, or 2) scaling AUM and writing larger checks into more established companies. (LINK)

The people who win deals are the ones who want to win them most.

Especially during bubbles, chasing deal volume makes people lose sight of the fact that only a small handful of deals matter every year. To that same point, there are only a small number of people you should actually be spending time with - chances are, you know who they are. You just need to spend more time winning the right to invest in them. (LINK)

The venture model only works when you are contrarian and right, but if you look around today, you see an industry that completely ignores the second part of the equation.

YC is consensus (even though their credibility is dropping by the day). “AI-enabled” is late consensus. Only backing former XYZ employees is consensus. “SF / NYC only” is consensus. If you want to avoid consensus investing, know more than anyone else (prepared mind), bet bigger than anyone else (increase the magnitude of your bet), or play different than anyone (non-traditional bets). (LINK)

Secondaries investing has forced venture investors to act as traders. Knowing when to sell has become one of the most important decisions for any fund, and there is a correct framework to think about it.

If you’re compounding at 25% for 12 years, that turns into a 14.9X. If you’re compounding at 14%, that’s a 5. And the public market which is 11% gets you a 3.5X. […] If the asset is compounding at a venture-like CAGR, don’t sell out early because you’re missing out on a huge part of that ultimate multiple. For us, we’re taxable investors. I have to go pay taxes on that asset you sold out of early and go find another asset compounding at 25%.” Taking it a step further, assuming 12-year fund cycles, and 25% IRR, “the last 20% of time produces 46% of that return.” (LINK)

If your best assets are compounding at a rate higher than your target IRR (say for venture, that’s 25%), you should be holding.

That said, if a single asset accounts for 50-80% of your portfolio’s value, do consider concentration risk. And selling 20-30% of that individual asset may make sense to book in distributions, even if the terms may not look the best (i.e. on a discount greater than feels right). (LINK)

Narratives hype cycles determine markets, and narratives drive clusters of talent, customers, and capital.

If you are a founder or investor, you need to understand where we are in narrative hype cycles before you make any micro-level decisions. GTM strategy, hiring decisions, positioning - they are all downstream from where a company is in the narrative hype cycle. (LINK)

Private is the new public.

Private tech companies valued above $1B (~1,300 companies) now represent roughly $4.7T1 in aggregate value—about ~15%2 of the entire Nasdaq market cap, and closer to ~40% if you exclude the Magnificent 7. (LINK)

The best growth stocks are private (and unavailable to most).

Across public software, internet, and fintech, there are fewer than 5 companies expected to grow at over 30% in 2026. Whereas in just the last year, we’ve seen over 100 series B or later rounds for companies growing well in excess of 30%. (LINK)

Power law is now consensus.

Over the last 20 years, one of the most controversial and non-intuitive tenets of investing went from being non-consensus to consensus. The market now believes that the level of disparity between the super-outliers and the non-outliers is much, much greater than previously imagined. The best companies aren’t just 10X more valuable, they are 1000X more valuable. These companies aren’t just going to be unicorns, they have the potential to be trillion-dollar companies. And being in the right trillion-dollar company at any point along the journey is way more important than getting into a unicorn at a decent price. (LINK)

As revenue-per-employee becomes the new vanity metric, org charts change, and what used to be required is no longer needed.

Fewer management layers of people. More management layers of AI agents. Hiring fewer, but higher agency people. Generalists over specialists. A premium on AI fluency. (LINK)

Expect more Silicon Valley social norms to be broken.

This will continue as long as the sums continue to get bigger. Social shame isn’t worth it when you’re grifting at small scale, but when the opportunity is to make billions? The ever rising cost of private aviation can make people do strange things, especially when it’s earned in short timescales. (LINK)

The most mis-valued asset in the world are entrepreneurs in markets that are non-obvious.

If you’re looking to beat the market, you won’t find a better bet. (LINK)

If we were going to maximize returns, we would do it over a longer timeline.

The compromise is a typical fund cycle (10 years + 2 years of extensions). Most of the compounding comes in years 12 and onwards. (LINK)

Capital is not as commoditized as you think.

Not every investor dollar you take is worth the same. The right investors can open doors and see around corners; the wrong investors can blow up your company. If you’re a founder, you should date around before committing to any investors (it is a decade-long partnership after all). (LINK)

Every investment firm has a limit to scale.

Finding that limit is an expensive process. I personally believe we are in the late innings of many realizing that. (LINK)

The career risk of an asset owner forces AUM scale.

Larger funds bet more on the front end (fees); smaller funds bet more on the back end (carry). (LINK)

Great GPs want the freedom to not think about money.

Good GPs just want to make money. (LINK)

Likability is a proxy for being reliable.

Likability works in private markets. (LINK)

Investing in any asset class is all about longevity.

You can be the best at what you do for years or even decades, but your strategy can blow up in your face at any time. The longer you stay in the game, the more impressive it becomes. (LINK)

Investment managers don't actually want the best returns; they want to do things that make them feel clever, interesting, or different.

The best trade over the past decade has been buying BTC, yet billions of assets are owned by funds that underperform relative to the S&P. (LINK)

There are asset managers, and there are investors.

Explaining that sentence would require a book. (LINK)

LPs that underwrite seed funds to 5x, which <5% of GPs can actually achieve, are engaged in self-harm.

In order to hit 5x, GPs are incentivised to take excessive risk. To get over that hurdle, they focus on maximising ownership, greater concentration, and competitive themes that promise rapid growth. (LINK)

There are only four ways to win in venture today: 1) structural inefficiencies, 2) deeper information asymmetry, 3) non-redundent sourcing networks, and 4) speed.

If you don’t have (at least) one of these, your days as a fund are limited. (LINK)

“Learn to code” is no longer sound advice, and for the first time in a long time, software engineering jobs are drying up.

2023 was the first year since Y2K when the number of software engineering jobs shrunk. Growth has resumed this year, but it’s at least possible that a long-term flattening of the growth curve is emerging. (LINK)

Hot markets = prescriptive approaches to investments = huge problem with atrophy.

This behavior, geared towards capital velocity, is focused on second order information and pattern matching. It is a prescriptive approach that informs what gets investment, displacing the first-order considerations about things like team, opportunity, valuation, market and strategy. (LINK)

Writing gives poor thinking nowhere to hide, in a world of infinite leverage, publicly sharing your thought process has moved from “nice to have” to “must have”.

This writing can be used to explain investment decisions, make predictions about where the world is going, and establish credibility in an industry where the natural thoughts are skepticism. Writing helps investors shortcut the waiting game by building trust with the right people, and that is why I believe many of the top-performing funds over the next decade will be built on top of an existing media presence. (LINK)

Seat-based pricing is going away; hybrid pricing is the new default pricing.

Reasons for hybrid pricing include minimal disruption, upsell paths, margin expansion, relatively good prediction. This has already created ripple effects for SaaS businesses, and it will continue to do so. (LINK)

Some reasons to believe concentrated portfolio construction is right:

Larger portfolios can signal an inability to pick, and LPs get more emotional attachment to a rockstar GP who promises a better picking ability than the masses. (LINK)

Pattern matching to emulate more concentrated funds like USV forgets the obvious that these others funds are not USV, and they attract world-class founders because of the brand they have built over decades. (LINK)

Larger portfolios = more work, and the value after the check is diluted the more portfolio companies have due to time and resource constraints. (LINK)

There's plenty of liquidity (even in venture), just not at the price you want.

The issue isn’t that there’s no liquidity for quality assets; it’s that most of the assets are low quality. This is the defining feature of venture and startups. Selling is downstream of having anything worth owning in the first place. (LINK)

MANG is eating VC.

Most of the capital commitment from these CVCs is coming via cloud / GPU credits. This allows Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Nvidia (MANG) to create a circular loop that boosts their top line while making these venture-backed companies more reliant on their own services. (LINK)

The end of SaaS.

SaaS is not dead, but the playbooks that created wealth over the past two decades of software investing have completely changed. How does this change venture dynamics when the majority of VCs are stuck balancing an existing portfolio of software business while looking for new companies to replace them? (LINK)

Secondaries are eating venture.

Anybody in the secondaries business has been killing it over the past few years. Everybody needs liquidity, and if you can provide that liquidity, you are a price maker. (LINK)

Increased competition for capital + fee-free co-investment opportunities has created quiet fee reduction for some funds.

Low-fee asset managers like Vanguard have introduced alternatives products to their clients. SPV leads have offered zero-fee SPVs to HNWIs and family offices. (LINK)

Junior VC roles are dying.

It has become harder to justify an analyst salary, and any investor below the partner-level is either fighting to keep their job or figuring out how to increase their earning potential so they don’t have to be reliant on their existing employer. (LINK)

Megafunds have become LPs and are seeding the next era of emerging managers.

Many of today's megafunds LP into the new era of emerging managers in order get visibility into their underlying portfolio, have ROFR to the breakout companies, + the ability to preempt the best with larger checks into later rounds. (LINK)

The death of the 10-year fund lifecycle.

Unicorns are staying private for nearly a decade on average, and ~40% are taking even longer. As this has played out, fund managers have been forced to deal with liquidity risks, extended returns, and impatient LPs. (LINK)

Slow paper is better than no paper.

Limited partners investing in slower-deploying funds achieved a net IRR of 11.6%, compared to 10% for those in the fastest-deploying funds. (LINK)

Megafunds are looking at public listings.

As AUM swells (Blackstone’s at $1 trillion, Apollo’s pushing $700 billion, GC’s at $30 billion), finding enough deep-pocketed LPs gets tricky. Going public taps a broader pool - retail investors, institutions, and others. (LINK)

Endowments are facing outside pressure.

Endowments play a huge part of the VC equation, and they represent 15-20% of LP capital. That number looks to be going down due to endowment taxes, NIL, DOGE, + a lack of DPI. (LINK)

Picking up venture “roadkill” is one of the most lucrative opportunities today.

There is a severe lack of DPI especially in the middle of the portfolio. There are tons of founders who are stuck (raised too much, not hitting growth targets, bad pref stack), who can’t quit. (LINK)

Seedstrapping and the reduced need for MVP capital.

Capital efficiency is more achievable than ever, product risk has decreased, founders want more control, and it creates better outcomes for investors (only if you're early). (LINK)

The unicorn factory model is dead.

Predictable public demand for the “polished” unicorn is gone. At the same time, the VC factory model created asset managers and eliminated a lot of the venture craft. (LINK)

‘Buy and hold’ is being replaced by ‘buy and maybe sell’.

Timelines have moved from 7-10 years to 12-15+ years. The lack of liquidity has also put a higher emphasis on DPI, and new funds are not being raised unless the previous fund(s) have distributions to show. (LINK)

The unbundling of VC power is here, and it is accelerating.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the entire VC asset class was a small, connected group linked to Arthur Rock that acted as gatekeepers in a buyer's market. Founders needed significant capital for infrastructure; they had that capital. They invested in who they knew, proximity mattered (still does), and proximity at the time meant being based near San Francisco and Sand Hill Road. (LINK)

Starting a company got cheaper. This meant more companies being started, more winners being minted, and more allocations for VCs to compete for. This can also explain the chart in the section above with the growing number of investors since 1992. (LINK)

Monolithic (nameless) investment firms converted to feudalist brands. Monolithic brands stopped winning, and savvy funds started letting partners modularize and dominate different investment areas for the firm. This let individual contributors (the partners) win opportunities for the larger group (their funds). Sequoia, a16z, and Coatue are examples of this shift. (LINK)

The shift to feudalism gave more power to the partners, and the most ambitious partners started exercising this new change of power. As founders started prioritized who they were working with over what firm they were working with, many investors saw the larger opportunity to build their own firm, leverage their existing brand, and own the GP rather than taking a smaller amount of carry. (LINK)

In 2025, media and investing are becoming more and more intertwined.

Venture funds have unbundled, and more power is going to the individual investor. Especially for early-stage investors, it has become an expectation to share thoughts and opinions somewhere on the internet in order to increase your surface area. The best founders are choosing their investors on the basis of their distribution. (LINK)

Longer timelines to exit has TONS of ripple effects.

Delayed liquidity hurts LPs who manage to an IRR and even for Cash-on-Cash returns slows distributions which can be reinvested in VC and other classes. For the earliest funds (pre-seed, seed) this means instead of 10 year fund cycles for LPs, you’re seeing closer to 15, which fundamentally changes LP calculations about the asset class. (LINK)

GP incentives are not what they used to be.

In the past, good seed funds got rich off carry. With megafunds, you get really rich off fees regardless, which can impact all sorts of incentives to keep private marks high (TVPI!) while you raise new funds. For more modestly sized pre-seed and seed funds, the returns are where you hope to strike it rich. So DPI matters sooner. (LINK)

YOLO, not HODL.

The old venture playbook meant that VCs are investors, not traders. They hold until the founders and company exit. In today’s world, VCs increasingly are traders. Every venture firm who has held crypto tokens/coins have made buy/sell decisions and some even have a trading desk equivalent. (LINK)

It is easy to forget that the extraordinary returns generated by technology have been generated almost entirely by only a few dozen companies globally.

Almost none of them fit into an easy to define category with multiple winners. This power law of returns dictates that the vast majority of startups in hyper competitive markets will fail. Tesla was started in an era when cleantech was “dead”. Canva was created when consumer was “dead”. Vercel was started when it was believed open-source couldn’t close enterprise contracts. (LINK)

The VC factory model created asset managers and eliminated a lot of the venture craft.

Fund sizes grew, and fees are more predictable than returns. (LINK)

Predictable public demand for the “polished” unicorn is gone.

The combination of adverse selection, the best companies staying private longer, and dumping SPACs / low-float IPOs on the masses has created huge distrust in all tech IPOs. (LINK)

There are too many early-stage VCs (especially early career ones) whose incentive is to spend money, not make money.

Junior investors advance by doing deals and deploying capital. Making money on those checks is an afterthought - who knows if you’ll be around in 7-10 years anyways? (LINK)

Different LPs assign different weights to each of the jobs of a GP.

Some LPs will place zero importance on a few of these, and others will vary their weightings depending on the macro. Some may heavily weight the ability to co-invest or join on SPVs. Certain funds will sell their fund-of-funds product as subservient to their co-investment strategy. Endowments or institutional LPs will more heavily weight traits that help the GP stay in the game (e.g. capital raising) than a family office. (LINK)

Productised capital can come in many forms.

It can come through media and storytelling, or distribution power through existing portfolio companies, or brand, or structured networks (think YC’s book face), or a bunch of other things. (LINK)

Track record coming from a megafund is largely irrelevant for most (not all) of these spinout GPs.

Were they able to win allocations because of the brand of the firm they worked under, or were they able to win because the founder chose to work with them as the partner leading the deal? (LINK)

None of the resources from a megafund transfer over when you have to do it alone.

Operating from a constrained set of resources is a totally different environment and skillset that is not built from working in an environment with an abundance of resources at your disposal. (LINK)

For most GP spinouts, the right to win evaporates without the megafund.

There are only a handful of investors who can command the right to win allocations on their name alone. Not saying that all spinouts lack this right, but I am saying that it becomes a LOT harder to win without billions in AUM and the potential for future follow-ons to dangle as a carrot. (LINK)

Everybody wants to back hot emerging managers; nobody wants to pay what it costs to back those emerging managers.

If you’re not laser-focused on venture capital as an asset class, you will suffer from adverse selection. This principle applies across all asset classes, but it’s especially pronounced in venture, where the gap between "good" and "great" is massive. A "good" manager maybe creates the same returns as the S&P (more data on this below); a "great" manager can create returns that you can’t find in other asset classes. (LINK)

As knowledge becomes more and more commoditized, unique networks of people are one of the last sources of alpha left.

Unique networks “future-proof” a person by giving them access to opportunities, founders, customer intros, and talent. I would argue this has always been the case, but it now that knowledge is no longer a moat, I would argue bringing a network is one of the only things that matters. (LINK)

As the old guard of venture firms have become asset managers, the game they are playing has shifted.

It is no longer viable for them to scour the universe for the best seed opportunities; instead, it makes more sense for these mega funds to let others do that work so that they can curate the best opportunities from there. (LINK)

In fundraising, you should be prioritizing dialogue > pitch meetings.

Give people a reason to talk to you so you can passively give them updates (ideally showing momentum) instead of asking for more time on their calendar for another pitch. Nobody likes being pitched. (LINK)

“Over the next decade, how you create, transform, source, store, and distribute tokens will define nearly all companies on the planet.”

Every meaningful business becomes a “token factory”: supplying, building, or orchestrating tokens (data, identity, money, expertise) that feed AI agents. The real power shift is in agents that can read tokens, act with them, and reinvest what they learn into better tokens. (LINK)

The formula for trusted brands: Brand promise > emotional benefit > logical benefit > features.

Selling on emotions is more powerful than selling on logic. Selling features is a wasteful use of marketing dollars. IMO, 90% of companies pitch features without first nailing the components before. (LINK)

More from me

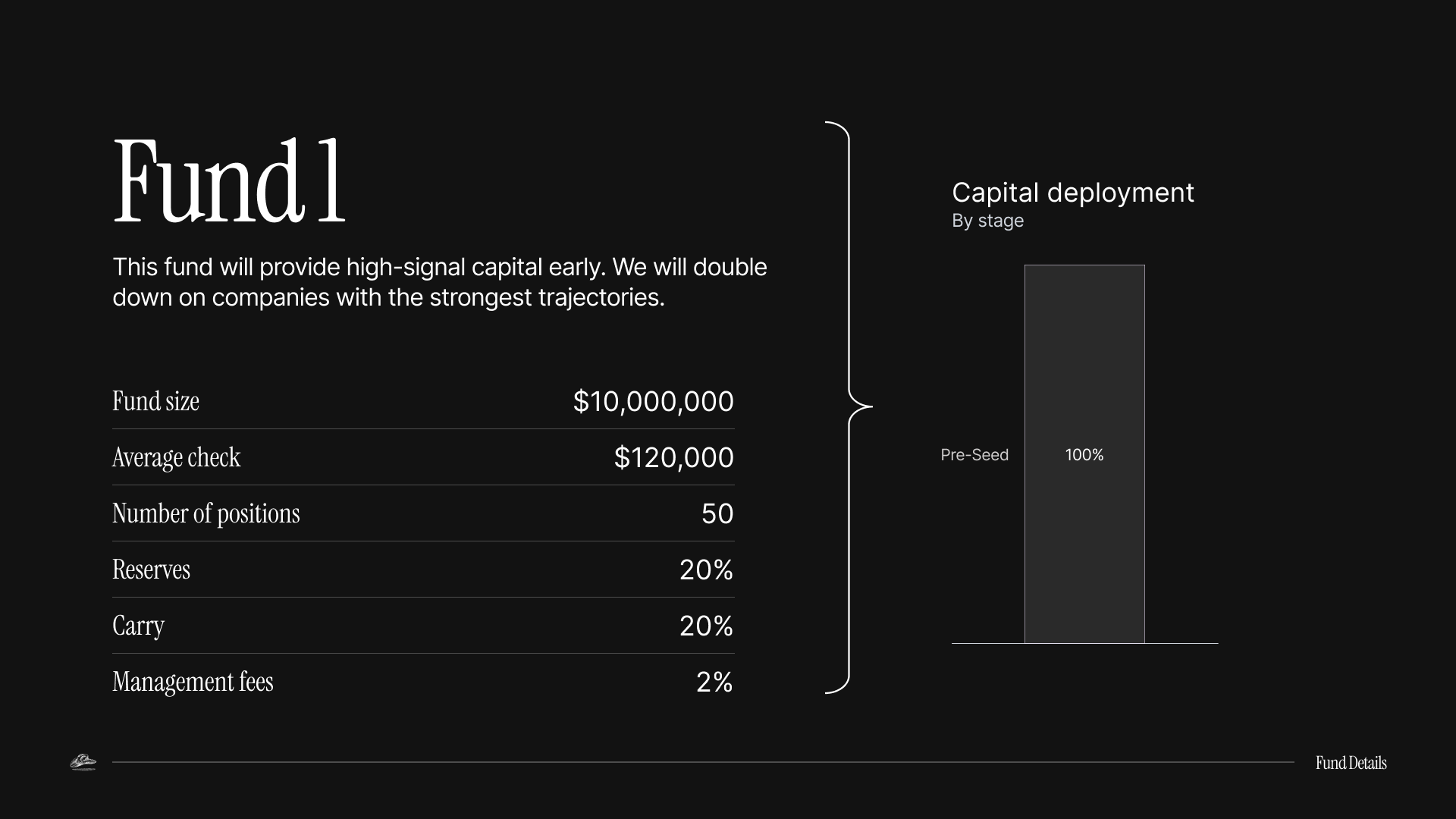

~95% of these takeaways are from my vantage point as I parlay this newsletter into the fund I am building.

If you are interested in learning more about how I am thinking about the strategy, I have included some links below.

If you are interested in learning more or participating, I’d love to talk.

P.S. We have a bounty system for LP intros.

If you can broker the intro and put us in touch with somebody here, we’ll compensate you for it.

Share Confluence.VC

Share this newsletter with your friends, or use it as a pickup line.

1 referral

Free month of Insider

5 referrals

Free month of Operator

👉 Your current referral count: {{rp_num_referrals}} 👈

Or share your personal link with others: {{rp_refer_url}}

Thanks for reading this far and giving us a little bit of your attention this week. Feel free to unsubscribe whenever this stops becoming valuable to you.

Paywalls are the WORST.

This will be the last time you ever see one of these from us if / when you upgrade below. We've even included a welcome offer for you ...

Claim your welcome offer ...Here's what else a paid subscription gets you:

- 5x posts / week (20x posts / month)

- 2x / month investment memos on pre-seed companies we find interesting

- Market maps on up-and-coming verticals (with company data)

- Database of 2,000+ venture capital firms with firmographic data